Politics & Society

Powerfrauen?

How Germany’s Political Parties are Approaching the Question of Female Representation

This weekend, Saskia Esken and Norbert Walter-Borjans were named the new leaders of Germany’s Social Democratic Party (SPD) after a runoff election against Klara Geywitz and Olaf Scholz. The candidates partnered up in male-female duos as part of the center-left party’s efforts to address longstanding gender imbalances.

Most children in Germany do not remember a time when their nation was not led by a woman, since Chancellor Angela Merkel took office in 2005 – 14 years ago. However, many of Germany’s political parties still struggle to promote women at the local, state, and national level.

After the percentage of women in the Bundestag dipped from roughly 37 percent in 2013 to just under 31 percent in the 2017 federal elections, anxiety that the country is backsliding stirred new debates about women’s participation in politics.

The SPD

Germany’s center-left SPD elected its first female party leader, Andrea Nahles, in 2018. However, Nahles stepped down after just over a year, due to poor results in the European Parliament elections and waning popularity.

Compared with some other parties, the SPD is doing well in its efforts to achieve equity. Close to 43 percent of the SPD’s 152 seats in the Bundestag belong to women.[i] However, women account for only 32 percent of SPD party members,[ii] and party leadership knows that serious changes are needed.

One such effort is the new system of requiring candidates for the position of party leader to team up in male-female pairs, to ensure a gender balance at the highest level. This policy has been heavily criticized, as many believe that some of the female candidates do not have the experience needed to succeed on the national stage. Many of the party’s most prominent women did not run, leaving a host of lesser-known women in the race. Nowhere was that more apparent than with the partnership of Olaf Scholz and Klara Geywitz. Scholz – the nation’s vice chancellor and finance minister – ran with Geywitz, a relatively unknown member of the state parliament for Brandenburg.

Geywitz has even been attacked by members of her own party, like Harald Sempf, the treasurer of the SPD Brandenburg. Sempf told a news outlet that Geywitz was not right “for the front row,” and suggested that a less prestigious post might be a better fit for her.[iii]

Furthermore, some news outlets are not covering the candidates equally, adding to the perception that some of the female candidates are only there because of a quota. Reuters published an article entitled, “Germany’s Scholz tops SPD leader vote, but faces run-off,” which failed to mention that Scholz had a running mate both in the headline and the first 11 sentences of the piece.[iv]

For her part, Geywitz spoke up clearly against these attacks and omissions, noting that she does not plan to be “the piece of decorative lettuce on the side.”[v] However, proving that she is an equal partner would have been an uphill battle, had she won.

Party leaders also typically serve as the party’s candidate for chancellor. With a two-person ticket, the so-called K-question, or “chancellor question” remains. The SPD is currently polling at under 15 percent, so the chances are slim that the party will select the country’s next chancellor. However, if the situation changes and the party does need to select a candidate, it might be forced to confront the question of how equal the two leaders really are.

The Union

The SPD’s coalition partners, the Christian Democratic Party (CDU), and their Bavarian sister party, the Christian Social Union (CSU) are facing more extreme challenges when it comes to the gender balance. Although the CDU has been led by a woman for almost two decades (first Merkel, now Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer), the center-right party has struggled to attract female members. In 1991, 25.6 percent of the party’s members were women. In 2016, that number had risen to 26.1, only half a percentage point.[vi] Women also occupy only 21 percent of the party’s seats in the Bundestag[vii] and are poorly represented on the local and state level.

The topic of gender parity is a touchy one for the CDU/CSU, as they lost roughly a million votes to the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) Party in the 2017 election.[viii] AfD voters, party members, and politicians are overwhelmingly male – only 11 percent of their representatives in the Bundestag are female.[ix] Some in the CDU/CSU argue that the party must remain true to its conservative roots so as not to alienate their base and lose more men to the AfD. Others, however, argue that women are more important to the party than ever given that so many men have left, so more should be done to address women’s issues.

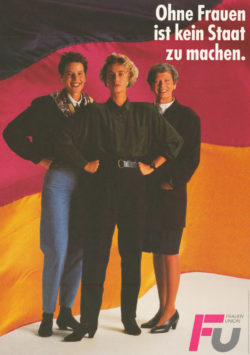

The Union has been hesitant to establish any binding quotas, opting instead for targets, which are often not met. Female members of the party, known as the “Frauen Union” or “Women’s Union,” pushed for a binding quota leading up to the party’s assembly on November 23, but their efforts were scuttled.[x] Similarly, a group of women from the CSU advocated for a 40 percent mandatory quota for female representation ahead of their assembly in October. The movement faced such significant pushback that the policy was never voted on, and they were forced to encourage a target instead of a requirement.

Success Stories

Two parties, however, set themselves apart in terms of female participation. Both the Left Party and the Green Party have long-established rules that require equal participation by women in many arenas. Women account for almost 54 percent of the Left Party’s seats in the Bundestag.[xi]

Germany’s Green Party has also long made gender parity a priority. In addition to establishing a double leader model (which is meant to achieve gender equality as well as a balance between different ideological camps within the party), the party also has strict requirements about equal participation of women in other key roles. Thirty-nine percent of the party’s members are women, [xii] and women account for 58 percent of the party’s seats in the Bundestag.

The Green Party’s longstanding commitment to parity has also perpetuated itself, in that women have been encouraged to rise through the ranks at the local and state levels. As a result, highly-qualified female candidates are ready to take on roles on the national stage.

Furthermore, the party has established systems to make sure that women’s voices are heard once they enter office. The Green Party has had a longstanding policy that speakers must alternate between women and men at the party’s assemblies. When more men would like to speak than women, the women vote to decide whether the conversation may proceed. Likewise, in cases where more women want to speak than men, men vote about whether to continue the conversation.[xiii]

Studies suggest that efforts like these may be needed. A survey by the Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women, and Youth of over 1,000 women in local office (across parties) found that 57 percent disliked the “political culture” in their work and 74 percent believed either completely or somewhat that women were not going in to politics out of fear of male-dominated structures.[xiv] Efforts to improve the experiences of women within the party may help encourage women to run for – and stay in – office.

2021

The Green Party’s strategy of supporting female candidates and politicians over the past three decades may end up paying dividends in the years to come. They have invested in women across all levels of government – from the local to the national – meaning that they have developed a system that produces highly-qualified candidates for important elections. Their focus on equity and gender balance also appeals to younger voters, who have been flocking to the party in recent years.

Although some of the Green Party’s policies might be unappealing to the center-right Union, others, like creating more supportive environments for women in government and encouraging women to run for local and state office, could help the parties in the long-run. As Merkel’s power wanes and Germany hurtles toward an uncertain election in 2021, some of Germany’s traditional “people’s parties” may need to reassess their approaches to the gender issue.

[i] https://www.bundestag.de/abgeordnete/biografien/mdbzahlen19/frauen_maenner-529508

[ii] http://www.bpb.de/politik/grundfragen/parteien-in-deutschland/zahlen-und-fakten/140358/soziale-zusammensetzung

[iii] https://www.morgenpost.de/berlin/article227155677/SPD-Politiker-Geywitz-nicht-die-Richtige-fuer-Vorsitz.html

[iv] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-germany-politics-spd-result/germanys-scholz-tops-spd-leader-vote-but-faces-run-off-idUSKBN1X50EL

[v] https://www.zeit.de/politik/deutschland/2019-08/parteivorsitz-spd-olaf-scholz-klara-geywitz-grosse-koalition

[vi] http://www.bpb.de/politik/grundfragen/parteien-in-deutschland/zahlen-und-fakten/140358/soziale-zusammensetzung

[vii] https://www.bundestag.de/abgeordnete/biografien/mdbzahlen19/frauen_maenner-529508

[viii] https://wahl.tagesschau.de/wahlen/2017-09-24-BT-DE/analyse-wanderung.shtml#16WanderungAFD

[ix] https://www.bundestag.de/abgeordnete/biografien/mdbzahlen19/frauen_maenner-529508

[x] https://taz.de/Der-CDU-Parteitag-und-die-Frauenquote/!5640416/

[xi] https://www.bundestag.de/abgeordnete/biografien/mdbzahlen19/frauen_maenner-529508

[xii] http://www.bpb.de/politik/grundfragen/parteien-in-deutschland/zahlen-und-fakten/140358/soziale-zusammensetzung

[xiii] https://antraege.gruene.de/44bdk/AenderungdesFrauenstatuts-56455

[xiv] https://www.bmfsfj.de/blob/93654/cc181cedaa0de9a08ae7faf4a71f0086/engagiert-vor-ort-kurzfassung-data.pdf