Politics & Society

The Transatlantic Relationship’s High Noon

The end of the film High Noon, a 1952 Western that rendered Gary Cooper's image synonymous with that of the lonesome, gun-slinging frontiersman, was equal parts controversial and iconic. Playing Sheriff Will Kane, Cooper’s town selfishly leaves him alone to face a band of outlaws. After he inevitably defeats the bad guys, the townspeople emerge from their homes, shocked at his victory. Disgusted at their cowardice, Cooper throws his sheriff star to the ground and retires to the desert.

Despite the film's massive success in the U.S., some theater-goers were shocked by this ending. They interpreted the scene as an allegory for Hollywood’s blacklisting of communist sympathizers. In their eyes, the cowardly townspeople unwilling to risk their necks to help Sheriff Kane resembled those in Hollywood turning away from their friends harried by accusations of anti-Americanism. John Wayne called the film “the most un-American thing” he’d seen in his “whole life.” Despite this controversy, the film’s shoestring budget, and production hurdles—the screenwriter was subpoenaed before the House Un-American Activities Committee during filming—High Noon thrilled U.S. audiences and became an indelible part of the Western film canon.

John Wayne called the film “the most un-American thing” he’d seen in his “whole life.”

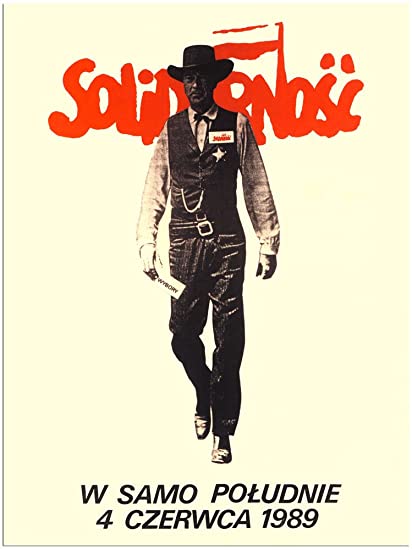

While High Noon’s ending stirred political controversy in the U.S., it came nowhere close to the power the image of Sheriff Kane invoked 37 years later in communist Poland. In 1989, an image of Sheriff Kane from the film’s ending became the centerpiece of the most iconic poster from the Polish resistance against communism. A still of Cooper takes up the majority of the frame; in his grip, instead of a gun, lies a folded ballot with the words Wybory (Election) visible. Below that, W samo południe: 4 czerwca 1989 (High Noon June 4th 1989).

This poster was part of the Polish Solidarność (Solidarity) movement’s campaign against the communist party and was used in a pivotal election that had been nearly a decade in the making. After Poland's communist government imposed martial law in 1981, many people associated with Solidarity were imprisoned and the country reached an economic dead end. This spurred the nation into protest, leading to mass strikes and the formation of an organized opposition against the communist government. Everyone was eager for a symbol to rally around. This poster was one of the most unlikely icons of Solidarity and emblematized an election in which they won 35 percent of the vote. It was considered a major victory and a turning point for democracy in Poland.

And so a film critiqued for being pro-communist in the U.S. gave rise to an anti-communist symbol in Poland a few decades later. How is it, then, that this image of the lonesome American gunslinger impacted both publics so profoundly in different ways?

And so a film critiqued for being pro-communist in the U.S. gave rise to an anti-communist symbol in Poland a few decades later.

In communist Poland, the Polish United Workers' Party dismissed symbols such as sheriffs, cowboys, and others from the American frontier as decadent, selfish, and western. Despite this (or rather because of it) a cult of the cowboy began to develop in Poland. The image of the free-thinking, self-reliant, and rugged cowboy deeply resonated with the Polish people. Poles began to covet Western films, and folk music began to feature Western themes, with songs like “The Sheriff’s Star” emerging as anti-communist anthems. Films like Wilcze Echa (The Wolves' Echoes) were produced in Poland, sneaking coded critiques against communism past censors in the guise of a Polish western.

By the late twentieth century, it began to feel as if the U.S. was not only Poland's most important ally in the world, but one which they could aspire to emulate and an emblem of individual liberty. Cooper’s Sheriff Kane embodied the rule of law and the conviction to stand up to bullies, even if no one was willing to help.

High Noon and Gary Cooper’s Sheriff Kane are just one of the innumerable symbols of the transatlantic relationship in the 20th century. From film and music, to art and literature, examples of how European and American values were strengthened through cultural exchange are scattered throughout history. Our animated video Cowboys in Krakow, which explores the history of the transatlantic relationship, touches on some of these small threads that have held this alliance together.